In 2013, North Carolina lawmakers set up a $10 million compensation fund for victims of state-sponsored eugenics. More than 780 people applied, claiming they had been forcibly or coercively sterilized by the state. Now, after an initial review, the state has decided only about 200 of those claims are valid, while more than 500 have come up short. The applicants are either denied outright or are asked for more information.

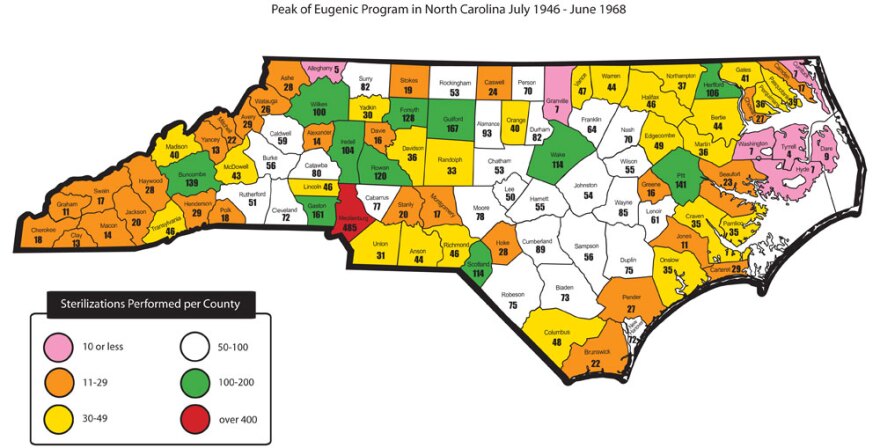

But we're also now learning that the state's eugenics program - once thought to be managed entirely by the North Carolina Eugenics Board - was actually much bigger. This fact presents problems for many seeking compensation.

Debra Blackmon's Story

In January, 1972, two social workers went to the home of Debra Blackmon. Blackmon was about to turn 14, and was intellectually disabled. It's hard to know exactly what was said, but court and medical documents have some details. They point out that Blackmon was "severely retarded" and had "psychic problems" that made her difficult to manage during menstruation.

The documents say Blackmon and her parents were counseled on the matter, and that it was in Blackmon's best interest that she be sterilized.

Debra Blackmon is 56 years old now. She's sprite and funny. She has a hard time remembering too many of the details, but she remembers that day in Charlotte Memorial Hospital.

"My daddy said, 'Please don't hurt [my] baby,' and he was crying," she recalls.

"We didn't find out until recently the extent of the surgery and what they did to her," says Latoya Adams. Adams is Blackmon's niece. She was born the year after Blackmon was sterilized and grew up hearing about it from older family members.

Last year, the General Assembly created a $10 million fund to compensate victims of state-sponsored eugenics, the movement that sterilized thousands of people deemed unfit to have children. Adams knew her aunt had been sterilized, she knew there were social workers involved, she knew a court had ordered the procedure. All the pieces seemed to fit. So, she went looking for documentation.

She came back with the mother lode, documents that told the whole story. There was a court order, and the consent form social workers presented to Blackmon's parents. Adams discovered documents that detailed the entire procedure from pre-op to discharge. The doctor labeled it a "eugenics sterilization." And while it was a relief to have the information, it was also remarkably sad.

"They were telling my grandparents the surgery was going to be minimally invasive," Adams says. "They told them it would be a tubal ligation. And they wound up doing a full abdominal hysterectomy ... on a 14 year old."

Instead of tying Blackmon's tubes - a potentially reversible procedure, the doctor removed her uterus. With all this evidence, Adams and her family thought they had a case. They filed the paperwork, and waited to hear back. The news wasn't good.

"The denial, the only thing it stated was that there were no records found and that her case was not approved by the N.C. Eugenics Board," says Adams.

What The General Assembly Expected Would Happen

Bob Bollinger, a lawyer representing Debra and a few other clients claiming to be victims of the sterilization policies, says that he doesn't think legislators had a full picture of the issue when they created the fund.

"I don't think the individual legislator understood there were a whole bunch of sterilization cases, of involuntary sterilizations, for whom paperwork would not be found in the Eugenics Board files," says Bollinger.

When the General Assembly set up the eugenics compensation fund last year, they gave three qualification requirements:

- You had to have been sterilized.

- You had to have been involuntarily sterilized, through force or coercion.

- The sterilization had to have occurred under the state-sanctioned North Carolina Eugenics Board, which operated from 1933 to 1977.

At the time, these seemed like reasonable qualifications. To most people's knowledge, the Eugenics Board was responsible for all but maybe a few sterilizations by rogue doctors. But, as it turns out, the Eugenics Board wasn't the only body performing sterilizations. Judges and social service workers at the county level were citing state law in the name of eugenics as well.

"And that's kind of become the fundamental problem here," says attorney Bollinger. "You have some old dusty filing cabinet in Raleigh that's full of Eugenics Board paperwork from decades ago, but yet you've got all these people sterilized involuntarily at the local level and their paperwork didn't wind up being preserved in the eugenics files in Raleigh, if it was ever there to begin with."

Bollinger says Debra Blackmon is not the only victim facing this type of situation in which medical records show a "eugenics sterilization" but there is no record of it in the Eugenics Board files. It's impossible to know exactly how many people fall into this loophole, though Bollinger says he's come across maybe a half dozen so far. He and other lawyers estimate there could be dozens or even hundreds such cases.

Settling Claims For The State

"A lot of people may have had this done under the auspices of local county groups. They're not qualified [for compensation.] They may think they're qualified, and they may have had this procedure done to them, but if it wasn't under the Eugenics Board of North Carolina, they're not qualified," says Graham Wilson.

Wilson is a spokesperson for the North Carolina Industrial Commission. The Industrial Commission is essentially a group of lawyers that works to settle claims on behalf of the state.

We asked to speak to the group's commissioner, Bart Goodson. Goodson has been responsible for making decisions on all 731 claims sent to the commission so far. We weren't allowed to speak with Goodson because the cases are still being processed, but Graham Wilson spoke on his behalf.

"Is it perfect?" Wilson asks. "No. But it's new ground. While it's not perfect and we've got some folks who are not happy, the Industrial Commission is doing everything it can under the law as written to make sure people who deserve compensation get it."

County Eugenics Boards?

The idea that sterilization was done at the county level implies that there were county eugenics boards making decisions about who should and should not be sterilized. That's not the case. Looking at Blackmon's claim, that decision was made by a district court judge, which is part of the state court system. That judge did not cite a county law, he cited a state law from 1963. In fact, an earlier eugenics law actually required county officials to seek out individuals they deemed fit for sterilization. And the state would pay for it.

So I asked Wilson, the spokesperson for the North Carolina Industrial Commission, "If all of the pieces of this puzzle exist because of state policy - doesn't that make the state liable?"

"That's hard to say," Wilson replied. "It's just something that was done. It was the way of the time."

I pressed him, noting that the required paperwork could likely not ever turn up, and Wilson said, "probably not."

I was curious why the law was written this way in the first place. Why were only victims who had files in the Eugenics Board records considered qualified, when many other people seemed to fit the bill, but were just missing a single piece of paper.

I called Representative Paul Stam. Stam is the Republican Speaker Pro Tem in the North Carolina State House. Basically he is the second-in-command to Speaker (and U.S. Senate Candidate) Thom Tillis.

Stam and Tillis worked together closely to get the final compensation bill passed in the house - a bill other legislators had been working on for a decade. Stam has written extensively on the eugenics program, and has expressed pride in getting the compensation bill passed. So I asked him "Were you even aware of the extent of the program? Did you know this happened outside of the eugenics board?"

Stam: That subject didn't even come up.

Eric Mennel: If you were to think about that now, is that something worth considering?

Stam: Interesting question. I don't make a policy decision because a reporter calls me.

Eric Mennel: That's fine. I'm not asking you to make a policy decision. I was just wondering would you consider it?

Stam: I consider everything all the time.

For the victims, it's frustrating. A program that was administered without particular care, where people were sterilized under state law without the state even knowing about it, is now trying to correct itself by being particularly strict and narrow. For Latoya Adams, it feels like a double blow.

"Everything is there, it's all in the paper work. But because you can't find a piece of paper saying it got approved by the N.C. board, you're not going to be compensated. I think it's sad. You've hurt her once, now I feel like you've turned around and hurt her again."

There is an appeals process - and Adams and Blackmon are working through that right now. If numbers hold, 213 people will split the $10 million, that’s about $47,000 each. But the way it looks, Debra Blackmon will not be among the recipients.

>>This 2011 story reports on then-Governor Bev Perdue's task force to study the issue and determine compensation.