Franklin County Public Schools are one of a handful of districts in the state bound by court desegregation orders. The federal orders are what helps keeps the schools among the most racially balanced in the state at a time when many districts are re-segregating.

In Franklin County, the orders date back to the sixties when federal judges across the south began stepping in to force integration.

The story begins in the Coppedge family household.

It was Christmas Eve of 1967, and Christine Coppedge and her teenage son were sitting on their living room floor, wrapping gifts.

They had just returned from Christmas service where Coppedege’s husband, Rev. Luther Coppedge, gave a sermon. As they wrapped and placed the presents underneath the tree, Coppedge and her son began hearing crackling sounds.

“What was that?” her son, Harold, casually asked.

“Probably some of the white kids shooting fireworks,” Coppedge reassured him.

Another sound rang out. Coppedge got up and checked on her husband who was sleeping in the room next door. As she made her way back to the living, a third pop. This time, she smelled gun powder.

“Hit the floor,” she said. “They’re shooting in the house.”

One of the bullets shot through the walls and into her husband’s room, barely missing him. Later, Harold opened the front door and shouted,"Coward!" as loudly as he could. They all knew what this was about.

Several Black Families Faced Harassment

“They were saying that I wanted to be white,” said Coppedge. “And I said ‘I don’t want to be white, I want to be just who I am. I just want my son to have an equal opportunity to have the same education as anybody else have. That’s all I want.’”

Harold was one of only two black kids at an all-white school in Franklin County. More than a decade after the ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, schools were slow to desegregate.

Following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Franklin’s schools—like many other southern school districts—adopted an integration plan called “Freedom of Choice.” In theory, it meant students could request seats at whatever school they want.

So, that’s what the Coppedge family did, and that’s when the harassment began.

“They killed the dog, they killed the cat, they put oil in the well, they put sugar in the tractor,” Coppedge explained.

Even the white neighbors—who were supposedly very nice—stopped talking to them in public.

Backed by the NAACP, the Coppedge family sued.

Segregated Schools: 'It was a way of life'

The Coppedges, along with several other parents, filed a lawsuit against the school board for discrimination in refusing to admit 20 black students to all-white schools. Eventually, the U.S. Justice Department stepped in, joining the families in calling for an end to segregated schools.

“It was a way of life,” remembered Charles Davis, a retired attorney for the school board. “I’m not saying it was good or bad, but it was a way of life and it’s what we all grew up in.

Davis said any swift changes to the schools would be hard—he wanted to take things more slowly.

“And what they wanted to do is come in and like flipping a light switch, flip it on, and it’s integration,” he said. “And the people in the county—white and black—had a lot of reservations about it.”

'You're going to help change our country'

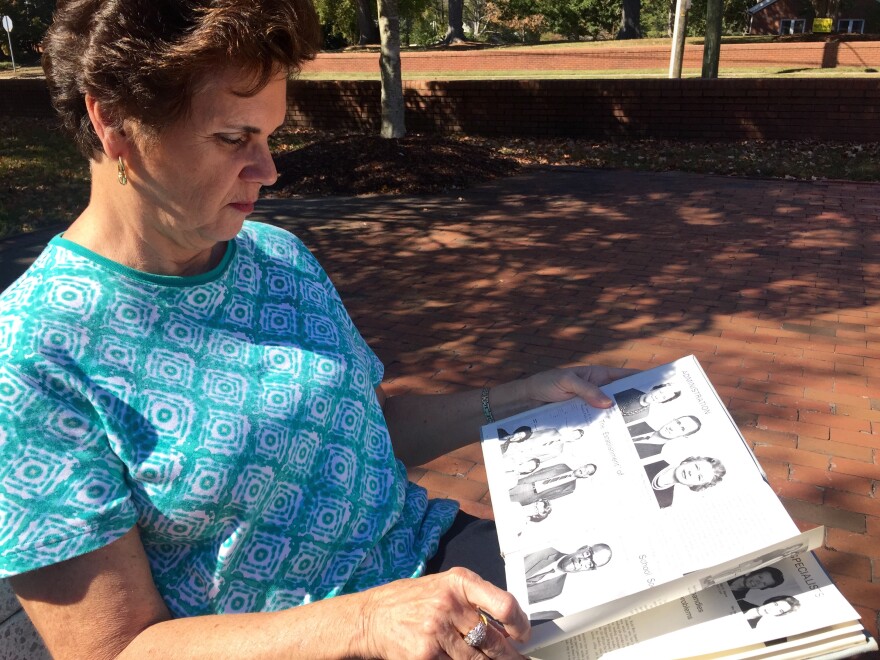

Black families had their names printed in a local newspaper if they signed up to send their kids to a white school. That pressured many students out of it, but not Pat Gill. She remembers a conversation with her dad.

“We were around the dinner table and he said ‘you are going to Louisburg High school, and you are going to help change our country,’” said Gill, who was 16 at the time.

Around that dinner table, she cried. “I was like ‘Oh I’m going to do something great,” she explained.

But it was lonely. She was one of only a handful of black students that year. She remembers kids jumping away from her, making gorilla sounds, throwing her books into bathroom stalls, laughing, taunting, ignoring her.

“What happens when you just get tired of this crap?” she said.

This is what happens. One morning, she and five other black kids decided they’d switch things up. They’d each take a different seat on the bus, instead of sitting together. Usually, the white kids refused to sit next to them, so this felt like a big deal, Gill explained.

Many of the white kids stayed standing, refusing to sit next to them. Gill said the event forced some of the white students to see their black peers as human.

“When you are angry and you want to do something to make a difference to say ‘no, I’m not a monkey and I got a brain, and I don’t smell, and I don’t want to touch you either,’” she said.

This all happened during Gill’s senior year in 1968. That summer, a federal judge ordered total desegregation. Shortly after, there was an editorial in the paper titled “A State of Shock.”

Total Integration In 1968

“There was definitely white flight. Definitely,” explained Cade Carter, a former student. “There were many students, probably from the wealthiest families who could afford to go to private schools in Raleigh.”

Carter was a white student who did not leave the public schools. She’s a self-proclaimed country bumpkin who worked in the farm. She said desegregation turned a lot of things upside down, but that she didn’t mind sharing a school with black students. She also remembers her principal.

“My opinion of Mr. Riggan is very different now as an adult,” she said. “When I was a student, I thought he was stupid. I did. He bent over backward to not discipline black students.”

“I don’t know that I was partial to one race or the other,” remembered Thomas Riggan, who’s now 83.

Recently, Principal Thomas Riggan walked through the halls of Louisburg High school, where he was principal for 18 years.

“I cannot tell you how many steps I made up and down these halls,” he said.

When Riggan first signed on to become principal in 1968, he had 500 students. After desegregation, he had 1200. Riggan pointed to the boy’s bathroom and explained how it was the scene of several clashes between black and white students.

“Someone would holler at me, ‘Mr. Riggin, there’s a fight in the bathroom!’ and I go running,” he said.

He’d pull the students into his office and tell them he’d give them another chance before he suspended them.

Still Under Court Desegregation Orders Today

These events happened almost 50 years ago. This imperfect, but triumphant moment, is what the Coppedge family had been fighting for, what they thought of when they endured the shootings and harassing phone calls.

But, as Christine Coppedge said, this was only the beginning.

“Things have not changed that much, some have changed, but we’ve got a long ways to go,” she said.

Today, Franklin’s schools are still under court-ordered desegregation until it fully eliminates the vestiges of discrimination. But it has made a lot of progress. It’s one most racially balanced districts in the state against a backdrop of increasingly segregated schools.

Each year, the district is required to send a report to the Department of Justice on the district’s racial statistics—everything from student enrollment to the makeup of the staff.

The last time the school board attempted to lift the orders was in 2002. The court declared that the district had achieved ‘unitary status’ in school transportation, extracurricular activities, school construction and facilities, student transfers and faculty desegregation.

The court documents, however, note that the district still needed to work on student assignment, staff desegregation and quality of education.

School officials said they’re actively working on bringing up student performance and that the court orders play a role in keeping them on track.

One way the district tries to make sure its schools are racially balanced is through a system called “Majority to Minority” transfers. Students who attend a school where their racial group is above the district average can transfer to a school where there are fewer students of their race.

As of this month, the district has made about 175 majority to minority transfers this school year in a system of about 8,500 students.

“If we keep the schools racially balanced, then I think the resources will stay balanced, and that’s what we’d like to see,” said Elizabeth Keith, vice-chair of the Franklin County school board.