Before he turned twenty-five, Van Morrison had written a rock and roll standard ("Gloria"), essayed arguably the greatest-ever Bob Dylan cover ("It's All Over Now, Baby Blue" — both with Them), made a top-ten American hit ("Brown Eyed Girl") and recorded two very different, very compatible LP masterpieces, Astral Weeksand Moondance — the former concerned with "childhood, initiation, sex, and death," per Greil Marcus in Stranded, the latter with rebirth, experience, love and living for its own sake. Yet nobody thinks of Morrison as a prodigy, because even as a young man he seemed older, somehow — somebody for whom experience doesn't count unless it's lived, and everything else is bulls***. For all the mysticism in many of his songs, his pithiest lyric, from "(Straight to Your Heart) Like a Cannonball," off 1971's Tupelo Honey, goes: "'Cause hearing it through the grapevine / Is just a dirty, rotten waste of time." The titles of his three most recent studio albums extend this tendency to the point of grumpy-old-man self-parody: Keep It Simple(2008), Born to Sing: No Plan B(2012) and — the height or the nadir, but more than anything inevitable — last year's Duets: Re-working the Catalogue.

Morrison is an acolyte and evangelist — a 2001 duet album with Linda Gail Lewis, younger sister of Jerry Lee, came about after they'd met during a Jerry Lee convention he'd attended as a fan, and he told interviewer Bill Flanagan in the mid-eighties that he'd considered becoming a teacher — and his music is in constant conversation with his inspirations. His own songs are littered with direct references: "Domino" nods to Fats, "These Dreams of You" is about a dream in which "Ray Charles was shot down / But he got up to do his best." And he has long performed the songs of his heroes in concert, sometimes in medleys with his own, which serve to highlight their similarities — and differences.

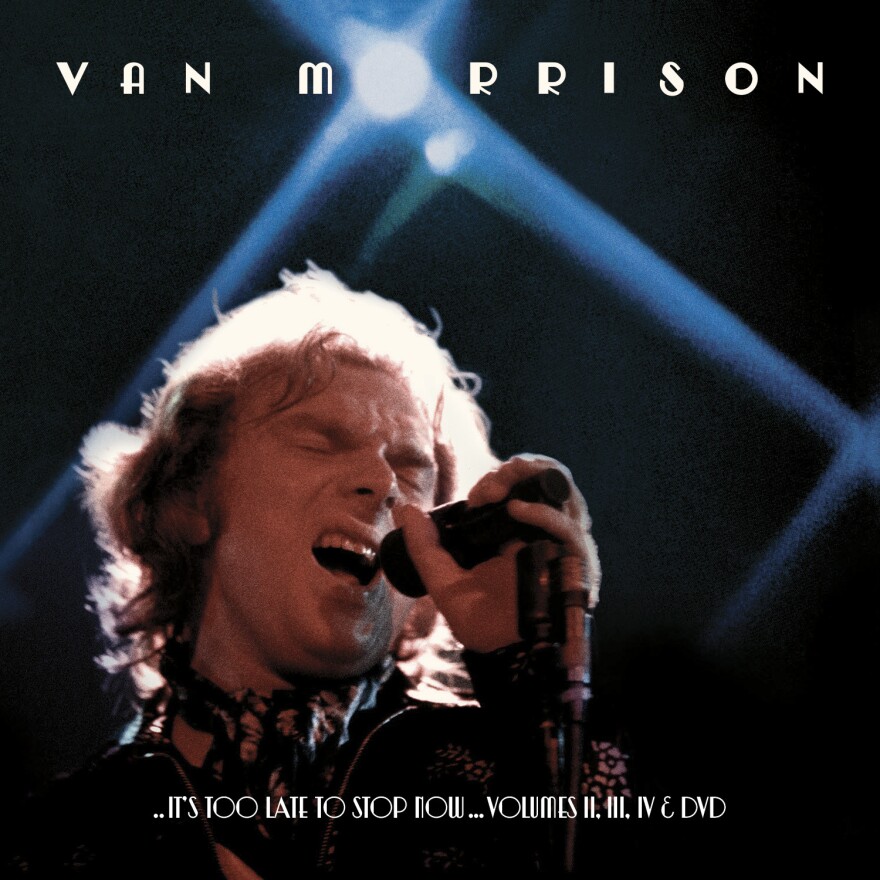

This reverence for his roots is documented most lavishly on It's Too Late to Stop Now, which Legacy Recordings has just reissued. A strong candidate for the rock era's greatest live album, the original double-LP was culled from eight performances in a trio of cities during a 1973 tour: at L.A.'s Troubadour on May 23; the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium on June 29; and London's Rainbow on July 23 and 24. Morrison left plenty on the floor, and much of it can now be heard on an accompanying box titled It's Too Late to Stop Now Vol. II, III & IV: Three CDs with 15 songs each, plus a DVD taken from the Rainbow on July 24, shot for British TV but left unseen till now.

Taken in full, it's overwhelming. Morrison was working with a ten-piece band he dubbed the Caledonia Soul Orchestra, including a pair of horn players and a string section, that could embellish every idea he had with aplomb, in particular loose-fingered pianist Jeff Labes and guitarist John Platania, the latter Morrison's ideal sideman: unflashy, sometimes a little gawky, but always genial and intensely sympathetic. Both are audible links to the bucolic Woodstock vibe that spawned Moondance (for more detail, see Small Town Talk, Barney Hoskyns' new rock and roll history of that upstate New York city), a vibe Morrison's mad perfectionism and rye-tinged skepticism so fruitfully undercut. Here's how perfectionist: Morrison wouldn't allow anything onto the original It's Too Latethat had a single audible error, nor any studio overdubs — all the way live or else.

The double-LP version of It's Too Latehas a deep coherency, but listening to the box we discover that he wasn't simply selecting the best version among many — he was choosing the ones that felt the most right together. The liberties he takes with the material on the double-LP always feel purposeful and deep in hand. But the box contains wilder, freer versions of some of the same songs, and in some cases they sound even better. The "Domino" from the Rainbow has a hurtling energy that's more electric than the more measured crowd-pleaser that appeared on the original double-LP; occasionally Morrison's singing is so staccato it sounds like an actual jolt. The version of Sam Cooke's "Bring It on Home to Me" from the Troubadour is soberer, and more wounded, than the one on the original album. And these aren't small changes, for the most part; even the handful of the box's songs that resemble the double-LP's eventually take different turns, and most of them are very different, from one another and anything else. Morrison's formidable commitment to in-the-moment energy, to creating something new every time out, is ferociously intense. It's daunting to realize that he could have chosen any number of other performances for the double-LP instead of the ones he did and gotten nearly as good a result.

There are many covers on the box set. He plays Louis Prima's comical "Buona Sera" and Hank Williams' "Hey, Good Lookin'" alike as New Orleans house-party jams, offers a pair of marvelously straight readings of the R&B-standard ballad "Since I Fell for You" and turns Kermit the Frog's "Bein' Green," of all things, into a passionate showpiece. But his choices of cover songs that made it onto the double-LP — a full one-third of the selections — amounts to a mission statement: Bobby "Blue" Bland's "Ain't Nothin' You Can Do" kicks it off, followed by versions of Ray Charles, Willie Dixon and two Sonny Boy Williamson songs in addition to Cooke. Each lives up to, without sounding remotely like, the original. He's sui generis even when he's paying tribute.

Which is part of the great Van Morrison conundrum. By any standard, he's the greatest white R&B singer ever — only he's not really R&B, for the simple reason that he's not really any one thing. "I'm a musician," he told Creem's Cameron Crowe the night of the Santa Monica Civic show. "I'm in music, not rock 'n' roll." Morrison is a Prince-level syncretist — jazz, folk, pop, rock, blues, even country (cf. 1971's Tupelo Honey) all come to the fore at various points, sharp and present and correct. But where Prince delighted in creating contrasting set pieces, Morrison constantly blends and alchemizes. Categorizing him, even a song at a time, winds up a fool's errand.

The other reason is that Morrison's never had much funk, and especially in hip-hop's wake funk tends to be the measuring stick for older R&B. His music is rooted in the era just before James Brown changed the rhythmic rules. Morrison's hardly devoid of groove: "I've Been Working," from 1970's His Band and the Street Choir, chugs so hard that a producer named Rayko turned it into a disco edit; a pair of ten-minute run-throughs of the same song from the 2013 box of Moondanceouttakes burn like contemporary James Brown and he covers Sly & the Family Stone's "Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)" on the 1994 live album A Night in San Francisco. But Morrison's beat swings more than breaks, and even before the lawyers clamped down, no prominent hip-hopper — not one — has ever sampled him, a serious anomaly for any presumptive greatest white R&B singer ever. (Beck doesn't count, sorry.)

The most hip-hop thing about Morrison may be that he's been bitching about record labels — Industry Rule number 4,080 — for nearly his entire career. For good reason, too, since gangsters affiliated with his then-producer Bert Berns broke Morrison's acoustic guitar over his head in 1967. That's not the only way the pop business disagrees with him: Few people with actual hit records have ever found the very idea of having a persona so distasteful. "I'd prefer to remain anonymous but that's not the way it is," he told Crowe. "You see it's not important who's playing it ... you're only a vehicle for what you're doing. You're a vehicle for music to come through." Later, he added: "I'm never satisfied with what I do. It's my job. It's my job to make music, and I'm not satisfied."

Listening to all four volumes of It's Too Lateis a reason to be grateful for the unrest. If the original double-LP gains power and focus from the setting the covers provide for songs spanning his career, from "Gloria" to 1973's Hard Nose the Highway, which came out shortly after the tour ended, the box explodes that context, even as Van's earthy blues principle grounds him no matter how flighty he gets. The Santa Monica version of "Sweet Thing," Astral Weeks' most ethereal song, starts jazzy and scatting before moving into an unexpected uptown strut on the coda, complete with a lyric change from "With your champagne eyes / And your saint-like smile" into "With your Coupe de Ville / And your Thunderbird wine" that transforms the idea of which type of "sugar baby" he might be singing to. On "Brown Eyed Girl" at the Troubadour, he drops a couple words per line for most of the penultimate verse before making absolutely sure we hear the line, "Making love in the green grass behind the stadium with you." Let's take him at his word on that, too — and note that the song was originally titled "Brown Skinned Girl."

It's Too Late to Stop Nowwas a culmination of Morrison's early career, from apprentice to master, but it also points to a very different artist than the one we know now. For one thing, Morrison's disconnection from the wider musical world hadn't yet begun making its way into his lyrics, something that started happening with increasing frequency in the '90s. In 1991's Hymns to the Silence, on the song "Take Me Back," Morrison finishes the title phrase: "To when the world made more sense." Once an old man, always an old man.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxNzg0MDExMDEyMTYyMjc1MDE3NGVmMw004))